About the alphorn

Texts about the alphorn, by Franz Schüssele, from various publications:

The alphorn

Alphorns are enjoying increasing popularity these days. There is now a large and ever-growing number of alphorn players not only in Switzerland, but also in Germany and Austria. Alphorn players can also be found in the USA, Canada, and Japan. In our highly technological and increasingly complex world, this simple natural instrument seems to embody simplicity and naturalness for many people.

The alphorn can be considered the prototype of wind instruments. Although it is classified among them in terms of instrument science due to its sound production, which corresponds to that of brass instruments, it occupies a middle position between woodwind and brass instruments. Its sound combines the powerful sonority of a brass instrument, such as a trombone, with the softness of a woodwind instrument, such as an oboe. While all other wind instruments have undergone technical developments over time, for example, in the shape of finger holes and valves, the alphorn has retained its original form without significant changes to this day. Today′s alphorns are on average about 3.5 meters long, and their length determines the single key they can be played in. Unlike a piano, for example, the alphorn cannot play a complete scale, but only a limited section of it, the so-called natural scale.

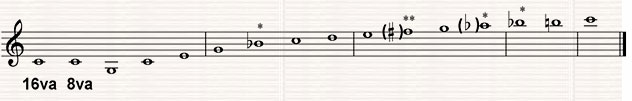

*The 7th natural tone B, the 13th A-flat, and the 14th B-flat sound too low in our modern tempered tuning. **The 11th natural tone F, the so-called "Alphorn-fa" (French: Fa=F), is significantly too high and lies between F and F-sharp. The 1st tone and the notes above the 12th are quite difficult to produce.

The approximately 12 individual notes are produced solely by varying lip tension and breath pressure, without the aid of technical means such as finger holes or valves like on other wind instruments. This requires great sensitivity, lip strength, and breath power from the player. Therefore, long and low notes are usually played on the alphorn, but with appropriate practice and skill, virtuoso, rapid tonal movements are also possible.

Building an alphorn:

Alphorns exist in straight and curved shapes.They used to be made in the same way throughout Europe. A tree trunk is cut in half lengthwise, the two halves are scraped out, and then reassembled. For curved instruments, the tree had to have grown on a slope. The two halves were sealed with resin or beeswax and tied together with roots, twigs, wire, or string. To seal the instruments, they were once placed in a stream or well before being played.

Today, alphorns are machine-cut into two halves. For ease of transport, they are usually made in three parts, which are joined with brass bushings, glued together with high-quality adhesives, and usually wrapped with rattan.

The mouthpiece used to consist of a carved recess; today, a separate wooden mouthpiece in the shape of a trumpet/trombone or horn is used.

The alphorn-center offers instruments from Europe′s leading alphorn makers for sale.

Sound generation, tuning:

Although made of wood, the alphorn is classified as a brass instrument due to its tone production, which is similar to that of brass instruments. It occupies a middle position between brass and woodwind instruments. Its sound combines the fullness and power of a low brass instrument, such as a horn or trombone, with the softness of a woodwind instrument, such as a clarinet or bassoon. It carries a great deal of distance and only fully unfolds at a distance, which is why alphorns only sound truly impressive outdoors and in large spaces, such as churches.

The different alphorn tunings:

The G-flat horn has a fine balance between a round, soft, harmonious sound and playing flexibility, which is why it has become universally accepted in Switzerland, except in a few cantons. The key of G-flat major sounds very soft and warm. This is probably one of the reasons why it was a popular key in the 19th century, the Romantic era. Swiss alphorn music with accompaniment, e.g., for organ or orchestra, is almost always written in G-flat. The G-flat horn is also typically used as a course instrument in Swiss alphorn courses.

The F horn sounds somewhat fuller and darker than the G-flat horn. When playing with other instruments, fellow players are often not particularly happy when asked to play in the somewhat uncomfortable key of G-flat. This is probably the main reason why most players in Germany prefer the F horn. Many players come from brass bands, and the alphorn is often played in combination with other instruments, which can then play in the technically favorable key of F.

The E horn sounds very charming and interesting. The bright key of E major is unusual for wind instruments. The high notes are easier to reach, but also more risky to play.

The E-flat horn has a very powerful, round sound. Due to its length, it is easy to blow high, but it is rather rigid and risky, making it really only suitable for a relatively slow playing style. It is only occasionally played in Switzerland and Germany.

The A-flat horn is very bright and flexible, making it well-suited for fast passages. It should not be played with a mouthpiece that is too small, otherwise it will quickly sound extremely harsh, almost like a trumpet. Higher pitches are still possible, but they no longer sound very alphorn-like, but more trumpet-like.

It is possible to play all of these pitches on a single horn using various intermediate pieces. The Alphorn Center offers such a horn.

Origin and distribution:

According to popular opinion, the alphorn is considered a typical Swiss national instrument and a Swiss "invention" limited to Switzerland. The first part of this statement can be considered undisputed fact, while the other two statements are not true.

When and where was the alphorn invented and played? a question often asked by wind players and alphorn enthusiasts, which unfortunately remains unanswerable and makes little sense. At some point and somewhere in the early days of humanity, one of our ancestors (or perhaps several of them) blew into a hollow piece of wood, a broken and somehow hollowed-out branch, or a small tree, thus bringing the first alphorn sound to life. On which continent or even in which country this occurred is no longer known today, but probably in every country, since such simple wooden wind instruments, similar to the alphorn, can be found worldwide, whether in Australian didgeridoos hollowed out by termites, Indian bamboo or other wooden trumpets, which the German composer and music theorist Michael Praetorius reported as early as 1619, or in African wooden horns, which are usually played horizontally like transverse flutes.

These instruments, which were quite short in their origins, had several functions as practical instruments: scaring away wild animals, enemies, and demons, mutual communication and message transmission (the "mobile phone" of the time), and at a higher stage of development, when humans began to utilize animals as "working instruments" for herdsmen, with which they drove and guided their cattle.

Shepherd′s horns of earlier times were only about half the length of today′s alphorns, which average about 3.5 m. Accordingly, they usually only played about 4-6 notes, in contrast to today′s long horns, which can play about 12 or more notes, depending on the player′s embouchure. However, these few notes were perfectly sufficient for their signaling purpose.

In Europe, alphorns once existed in a wide variety of forms, from Switzerland to Sweden, from Russia to Romania. Unfortunately, these simple natural instruments had almost completely died out in most European countries by the beginning of the 20th century including Switzerland! In 1805, just two players competed in the alphorn competition in Unspunnen near Interlaken, and the following year, only one. However, thanks to promotional measures, alphorn playing was quickly revived and made popular in Switzerland. The contributions of Ferdinand Fürchtegott Huber, Heinrich Szadrowsky, and Alfred Leonz Gassmann deserve special recognition here.

In Switzerland, the alphorn was first documented with certainty through the discovery of an approximately meter long wooden horn around 1400 near Meilen, and in the mid-16th century through the records of the Zurich naturalist Conrad Gesner.

In Austria, the monk of Salzburg first reported the wooden Kchuhorn in 1380; in Germany, a wooden horn from the 11th/12th century was found in Parchim (Brandenburg). An interesting slanted wooden horn is the Middewinterhorn, which is still played in the Dutch/German border region today and probably dates back to the time of the Celts. Thuringian shepherds played the wooden shepherd′s horn during pasture work until the 1970s, and an annual shepherds′ blowing competition took place until 1973. Every year on Christmas Eve, in the Black Forest town of Villingen, the Herterhorn sounds. Its shape is exactly the same as the Swiss alphorn and it is approximately 1.5 meters long. This custom dates back to a vow made by the people of Villingen in 1765 during a cattle plague.

In Poland, a large group of Ligawka glass players meet every year on the second Sunday of Advent for a blowing competition. Ligawka, Bazuna, and Trembita are the names of the Polish wooden horns, which are between 1.5 and 4 meters long. A variety of wooden horns can be found in Russia, the most interesting being the Siberian Payze, which produces its sound not by blowing, but by sucking air into the instrument. In Romania, you can find five different types of Bucium, which is usually played by women there, as they are responsible for herding the pastures. It is so popular that it was even featured on a postage stamp in 1961.

The alphorn in today′s musical styles:

While the alphorn was once a simple signaling instrument, in recent years it has evolved into a fully-fledged musical instrument, one that has a place not only in folk music, but in all contemporary musical styles.

The alphorn entered classical music very early on, as early as 1756 through the Salzburg court musician Leopold Mozart, father of the famous Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who composed a "Sinfonia Parstorella" for corno pastoritio (shepherd′s horn) and string orchestra. In the 20th century, the Swiss Jean Daetwyler and the Hungarian Ferenc Farkas wrote important works for alphorn and orchestra.

In jazz today, the two groups Mytha and The Alpine Experience of the Swiss trumpeter Hans Kennel set the tone with the alphorn, and the Zurich trombonist Robert Morgenthaler, in his group Roots of Communication, musically and cosmopolitanly combines the alphorn with folk instruments from other countries and continents in an improvisational manner. The alphorn is extremely rare in rock music, whereas it frequently appears successfully in (pop) pop music. The initial spark for this came in 1976 from the Pepe Lienhard Sextet with their hit "Swiss Lady."

In churches, alphorns were once used as a replacement for bells when they were silent, for example, during Holy Week. A whole series of sacred works for shepherd′s horn with choir and orchestra can be found in the 18th and 19th centuries in southern Germany, Bohemia and Moravia, and Austria, especially in Christmas music.

Curiosities in Alphorn Construction:

The alphorn clearly inspires the imagination of many hobbyists and craftsmen to build curious instruments outside of the usual forms. Horns made from tree trunks that are severely twisted and gnarled by nature have often been built, as have alphorns in the shape of trumpets, trombones, tubas, and saxophones, or even from sheet metal, glass, plastic, and papier-maché. An alphorn with three blowing tubes for three players has even been invented.The world′s longest alphorn, measuring 47 meters, was built in two versions: one by the Swiss alphorn company Josef Stocker and the other by the American Peter Wutherich.

Summary of the book "Alphorn and Shepherd′s Horn in Europe."